a documentary by Tatsuya Mori

Once celebrated as one of Japan’s leading composers despite being deaf, Mamoru Samuragochi’s name hit international news in February 2014 when a university lecturer named Takashi Niigaki revealed that he himself had been writing most of the so-called genius’s music over the past 18 years. Not only that, Niigaki claimed that Japan’s modern-day Beethoven wasn’t deaf at all. In the wake of typical media pandemonium, director Mori approaches and befriends the supposed hoaxer and his wife who are in hiding. Over repeated visits to their home, the truth behind the fiasco is unveiled – Or is it?

Samuragochi’s dimly-lit living room becomes a theater of unfolding riddles, where issues of fraud and plagiarism, media ethics and consumer appetites, Japan’s ritualized spectacle of public apology, and other tricky themes come on display. Eventually, the documentary leads us to question the truthfulness of the film itself, like a snake eating its tail.

JAPAN / 2016 / 111 min / with English subtitles

Trailer

The Director

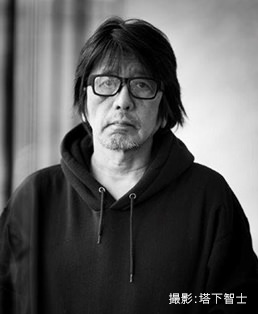

Tatsuya Mori

Filmmaker and writer, Mori is renowned for his taboo-crossing documentaries about the Aum religious cult _A_ (1998) and _A2_ (2001), which he shot in the aftermath of the 1995 Tokyo subway sarin gas attacks. _A_ premiered at Berlin International Film Festival’s Forum for New Cinema and showed around the world, while _A2_ was acclaimed and awarded at Yamagata documentary film festival. The controversial _311_ (2011) was made in collaboration with three other filmmakers, filming the 2011 Tohoku earthquake disaster. Winner of the Kodansha prize for non-fiction, Mori has published over 30 best-selling books on social issues and the media.

The Producer

Yoshiko Hashimoto(Documentary Japan Inc.)

About The Scandal

Mamoru Samuragochi was a self-taught classical composer with a severe hearing disability. The media dubbed him “Japan’s Beethoven.” He wrote symphonies and video game scores which were immensely popular. His “Sonatine for Violin” was to accompany a high-profile figure skater’s performance at the 2014 Winter Olympics before the scandal broke.

College teacher Takashi Niigaki became an overnight celebrity when he held a press conference and claimed that he himself had written most of Samuragochi’s music. He also declared that the composer could hear. He subsequently exploited his sudden fame through television appearances, magazine profiles, book publishing, and performances of his own music.

The media believed Niigaki. Samuragochi was roundly ridiculed on television and in the tabloid press. Humiliated and abandoned by his friends, he disappeared from public view.

From The Filmmaker

Suppose someone smiles. Hearing it described as either a smile or a grin would alter your understanding of the image. There’s no point debating which description is true – the choice of wording is determined by a writer’s intent or degree of empathy towards that smile (or the smiling person). If I disliked him, I might sense that his smile is a sneer. If I were fond of the person, the smile could feel like a beam. That is the nature of how information is conveyed. The contours of reality are never objective, fair truths. They can only be determined through perspective and interpretation. In other words, there’s always a filter of subjectivity in our perception of reality. We also know that surveys of so-called objectivity and neutrality shift with changing times and social systems. Indeed, trusting in such fickle estimations is insincere, irresponsible, and can be fatal.

Meanwhile, people working in the media are obliged to uphold “objectivity” and “neutrality.” Nevertheless (or therefore), as we write our articles and edit our images, we need to be mindful that we are never unbiased. It’s a cross we have to carry. But lately it feels like more and more reporters and television directors are blatantly claiming to be telling the truth. Words like “truthfulness” and “factuality” (alongside “deception” and “fabrication”) seem to come lightly and are used readily, especially in the front ranks of today's media.

The media is a mirror of what a society desires, because it follows consumer demand. Is Japanese society turning towards a world defined by simplified dichotomies? And it’s not just the media, either. Today's political discourse seems to exist in oscillation between rarified polar positions. It’s the same story. If Japan’s media is third-rate—which means we are living in a third-rate society—and so are its politics.

It looks like society, media, and politics are slowly nudging each other in a certain direction—towards uncomplicated analysis. To what will sell more. To what will get more votes. There’s truth and there are lies. Black and white. How painlessly straightforward it is. No messiness. It’s clear. Right and left. Justice and vice. Enemy and ally. Destroy the enemy. Justice shall prevail. Soon, we will be surrendering ourselves to the fever of the pack, and repeating that fateful error of the last century all over again.

There are infinite points of views and interpretations. Obviously, I have my own perspective and understanding of events but, ultimately, this film is up to you. You are free to make your own judgment. There is just one thing I want you to know. This world is free and plenteous and wonderful, and that’s because our views are diverse and many. (Tatsuya Mori)

Credits

Produced by Yoshiko Hashimoto 橋本佳子

Cinematography by Tatsuya Mori, Yutaka Yamazaki 山崎裕

Edited by Keita Suzuo 鈴尾啓太

Assistant Producer Shiori Tanaka 田中志緒理

Produced by: Documentary Japan Inc., Tatsuya Mori, TOFOO LLC, Dimension, Picante Circus

Distributed by: TOFOO, LLC 東風

5-4-1-306 Shinjuku, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 160-0022 Japan

Phone +81-3-5919-1542 / Fax +81-3-5919-1543 / Email info@tongpoo-films.jp

Contact: Asako Fujioka (DD Center) 藤岡朝子

For international affairs

Email info@ddcenter.org

Documentary Japan Inc.

Tel +81 3 5570 3551 / Fax +81 3 5570 3550

Japanese website http://fakemovie.jp